In a previous post I mentioned that the street corner Spätkauf (meaning late-night store) is the water cooler for residents of kiez (city neighborhoods). In this post, I’ll talk a little more about kiez.

Typically, this post would start by defining the word, kiez, but the use of the term in Berlin – a relatively new adoption of the word after the WWII – is fluid, and the nuance is also changing because of the recent rise in real estate values. I hope that giving a quick run down of the situation will communicate my understanding of the word.When I had only been in Berlin for about a week, I asked the first friend I made to take me to the trendiest spot in the downtown area. I grew up in Shibuya in Tokyo, so I was surprised at the very forlorn feeling of the drinking district that we had taken the trouble of getting to by changing subway cars. The street lined with 5-story, stone buildings had a German bar (Kneipe) in about 1 of every 10 buildings. There were few people walking along the dimly lit street. Unlike Japan where there are tons of bars around train stations and the area is lit up with neon at night, along the main street of clothing stores and other shops, the night was silent. Instead, most Kneipe are generally located a bit away from the main street. They are frequently lit by candlelight and have a warm, serene atmosphere.When you want to go somewhere that’s near a train station, just like in Japan you can just say, “Let’s go to Shibuya” or “Let’s hang out in Umeda,” but when you want to go to some out-of-the-way corner, you have to suggest it by name. Likewise, the name of the most thriving street or a landmark, like a church, is used to define a byway area, the kiez.The mood of a district is very much characterized by the people who live there. For example, Richard kiez has many artists, Winterfeldt kiez is home to many gay residents, and Beussel kiez is a neighborhood where many are unemployed. If I were to go on naming kiez, I would have to talk about architectural significances and locational backgrounds as well. That would be too long for this post, that I inevitably leave them out for now.

More than 10 years have passed since then. The relocation of the capital is nearly complete, and the number of tourists has doubled. Stylish cafés, art galleries, boutiques, and designer shops have sprouted, filling the spaces between the Kneipe. If an area can acquire the status of being stylish, then the real estate value also spikes. Recently, kiez branding by real estate agents has become excessive, and when you say something like, “I live in ○○ kiez,” you feel a sense of guilt, as if you’re participating in the rent hikes.

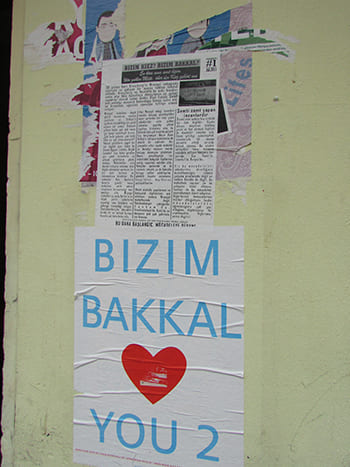

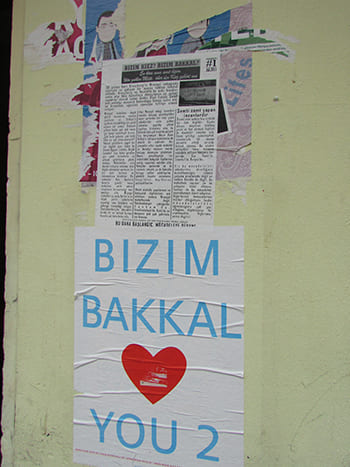

In June, a demonstration was held in Wrangel kiez against this kind of rise in real estate prices. Wrangel kiez was originally characterized by the working class and Turkish immigrants, but in the last few years it’s been transforming into a stylish, posh spot. A greengrocer in business for 28 years is about to be kicked out by tenants. During the demonstration, people gathered in the streets to protest against the coldness of the kiez branding. They made the greengrocery Bizim Bakkal (meaning „our grocery“) a symbol of the good old days of kiez and used „Bizim kiez” (our kiez) as their rallying cry.

So, if I were to try to define the continuing saga of the most inexpressible word, kiez, it would be “an area whose buildings/streetscapes have some kind of unique characterization that accompanies the desire for self-assertiveness and a sense of identification in residents who share a specific economic situation and political awareness.” Boiled down further, perhaps it would be “a neighborhood that inspires a back-street attachment.”

In June, a demonstration was held in Wrangel kiez against this kind of rise in real estate prices. Wrangel kiez was originally characterized by the working class and Turkish immigrants, but in the last few years it’s been transforming into a stylish, posh spot. A greengrocer in business for 28 years is about to be kicked out by tenants. During the demonstration, people gathered in the streets to protest against the coldness of the kiez branding. They made the greengrocery Bizim Bakkal (meaning „our grocery“) a symbol of the good old days of kiez and used „Bizim kiez” (our kiez) as their rallying cry.

In June, a demonstration was held in Wrangel kiez against this kind of rise in real estate prices. Wrangel kiez was originally characterized by the working class and Turkish immigrants, but in the last few years it’s been transforming into a stylish, posh spot. A greengrocer in business for 28 years is about to be kicked out by tenants. During the demonstration, people gathered in the streets to protest against the coldness of the kiez branding. They made the greengrocery Bizim Bakkal (meaning „our grocery“) a symbol of the good old days of kiez and used „Bizim kiez” (our kiez) as their rallying cry.  So, if I were to try to define the continuing saga of the most inexpressible word, kiez, it would be “an area whose buildings/streetscapes have some kind of unique characterization that accompanies the desire for self-assertiveness and a sense of identification in residents who share a specific economic situation and political awareness.” Boiled down further, perhaps it would be “a neighborhood that inspires a back-street attachment.”

So, if I were to try to define the continuing saga of the most inexpressible word, kiez, it would be “an area whose buildings/streetscapes have some kind of unique characterization that accompanies the desire for self-assertiveness and a sense of identification in residents who share a specific economic situation and political awareness.” Boiled down further, perhaps it would be “a neighborhood that inspires a back-street attachment.”