More than a hundred years ago, an association between Portugal, Spain, and France formed in Madrid to sign an international agreement.

The document was designed to protect each of the countries from profiteers who made money by forging place of origin information on counterfeit regional wines.Two of the world’s top three fortified wines come from Portugal—Madeira wine and port wine. The third is sherry, which comes from Spain (Italy’s Marsala wine, made in Sicily, is sometimes said to be the fourth type, but I’m omitting it from this list since it is actually modeled after Madeira wine). Needless to say, France had already made a global name for its champagne, cognac, and other alcoholic beverages, so the three countries wanted to make a statement that they would not tolerate counterfeit versions of their regional brands either. The agreement was ceremoniously titled The Madrid Agreement for the Repression of False or Deceptive Indications of Source on Goods of April 14, 1891. Japan joined after World War II, in 1966, forcing products like Yajirushi Champagne Cider and Akadama Port Wine to change their names. Iichiko shochu probably just slid by when it changed “cognac” to the name of the former French emperor in its popular tagline, “the workingman’s Napoleon”.Incidentally, there was another agreement signed around that same time. The purpose of this one was not to protect production areas, but trademark designs. This one was called The Madrid Agreement Concerning the International Registration of Marks of April 14, 1891. Today, it has nearly a hundred national signatories, making it possible to protect trademarks in all of these countries using a single registration process. Many high-end Japanese products recognized around the world are part of the agreement, as are their manufacturers—and since it is designed to protect their names, you wouldn’t think that anyone would try to register anything like “sushi” or “udon”… right?Last year, however, out of the blue, a lawyer filed a warning to a popular udon shop in Barcelona run by a Japanese. The document ordered him to stop using the word “udon,” since it was a registered trademark of a Barcelona company filed in 2003. This unreasonable request was not limited to the shop name, but included all internet and media content as well. The circumstances would certainly be different if “udon” were an international trademark.Going forward, if Spanish restaurants and bars were to register trademarks like “Butaman” or “Doteyaki” before setting up shop, it would probably put an end to the source of the trouble. Iberian pork has been gaining recognition as of late, so perhaps Japan should use the Japanese word for pork and trademark it as “Ibericobuta!”

An authentic Iberian pork tenderloin

An authentic Iberian pork tenderloin The “Iberian piglet” display in village of Jabugo, where Iberian pork originated. This display is in front of a longstanding ham shop called La Cañada.

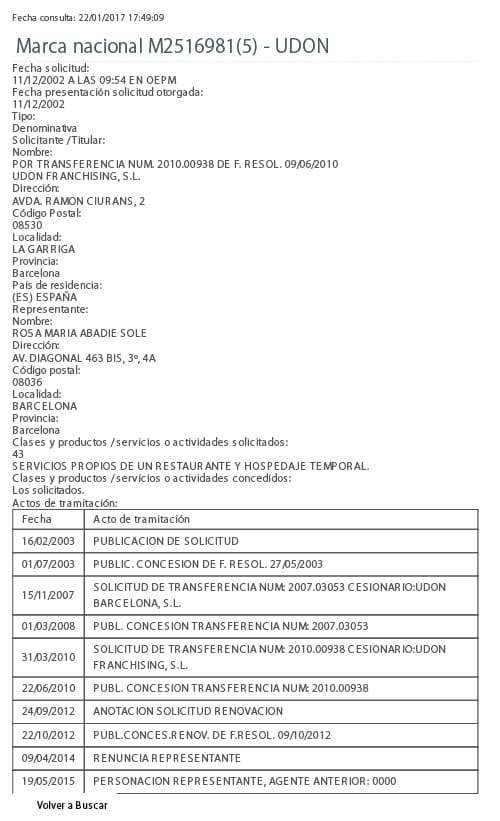

The “Iberian piglet” display in village of Jabugo, where Iberian pork originated. This display is in front of a longstanding ham shop called La Cañada. Udon trademark information by the Oficina Española de Patentes y Marcas (Spanish patent and trademark office)

Udon trademark information by the Oficina Española de Patentes y Marcas (Spanish patent and trademark office)