Terms like these often make an appearance around this time of the year, but if you live overseas, it’s no simple matter to go back to your family home, so if you do go back after being away for some time, you start thinking six months beforehand about who you’re going to meet, when and where, as well as what you’re going to see, buy, and eat, to narrow down your itinerary.

Even if for outward appearances the main purpose of your trip is to see your relatives by blood and marriage as well as your friends, to look good, what you really enjoy might be the food. Yet, living in Spain with the current Japanese food boom means you can now enjoy the flavors of Japan here to some extent, and the diet I eat when I’m back in Japan has changed partly because of laziness syndrome attributable to aging. Nowadays, unlike in the past when I used to eat at renowned restaurants listed in gourmet guides that serve Japanese cuisine, tempura and sushi, I don’t put on a big front but seek out ordinary good-tasting food, like the various new kinds of sandwiches that convenience stores keep coming up with, or potato croquettes from the butcher’s shop, or ramen at the good old neighborhood ramen shop in the hometown where I was born and raised.

The taste of Japan I am looking forward to this summer: Edamame (green soybeans), the best snack to go with beer at the height of summer. “Edamame” 500 g, 1.6 euros (about ¥210)

The taste of Japan I am looking forward to this summer: Edamame (green soybeans), the best snack to go with beer at the height of summer. “Edamame” 500 g, 1.6 euros (about ¥210)And of course there is the irresistible pleasure of an ekiben (lunch box for train trips), as well as the moment of joy when, sitting in your seat on the shinkansen with the generous array of delights in the local ekiben and an assortment of the drinking snacks that you see hanging up in station kiosks, you pull the tab on a can of chuhai (mixed shochu drink) with a “pffft” to start. The shinkansen experience gives you a mini onboard banquet, the pleasure and pride in the quick and respectfully careful manner of the onboard cleaning team, and the overwhelming physical awe of the Nozomi screaming past in front of you at terrific speed while you wait on the platform. So it is not merely a means of getting from A to B. Along with a “100-yen shop expedition,” it is one of the major reasons for coming home. In 1964 we proudly showed to the world the Japanese shinkansen in time for the Tokyo Olympics. The Tokaido Shinkansen connected Tokyo and Osaka, a distance of 515 km, in 4 hours (current shortest time 2-hours and 22-minutes). By the way, in 1992, the year of the Barcelona Olympics, Spain unveiled the AVE* high-speed rail connecting Madrid and Seville (472 km) in 2-hours and 45-minutes, which is now 2-hours and 20-minutes at the quickest.The Spanish high-speed rail started 30-years later than Japan’s, but the circumstances surrounding their launches were similar.Speaking of similarities, just like in Japan, the Spanish high-speed rail gauge differed from the conventional rail gauge. Both the shinkansen and AVE rail gauges are 1,435 mm, which is the international standard, but the conventional Spanish rail gauge is wider (1,668 mm) while the Japanese rail gauge is narrower (1,067 mm), so in both countries, if train services were to continue between high-speed and conventional lines, services would have to change carriages, an additional rail would have to be laid making for 3-rail railways, or the carriages would have to be able to change axle length. In fact, while the idea of this third solution – carriages that can change axle length – was raised in Japan with a train called the Free Gauge Train (FGT), Spain already had such trains in 1968. A means of changing carriage axle length was needed to allow trains to pass easily and quickly between the neighboring country, France, whose rail gauges differed. Initially only the unpowered carriages changed axle length and the locomotive had to be changed over to one that fitted the rail gauge. However, nowadays there are trains with locomotives at front and rear, and trains with locomotive carriages, so now they can all change axle length automatically.

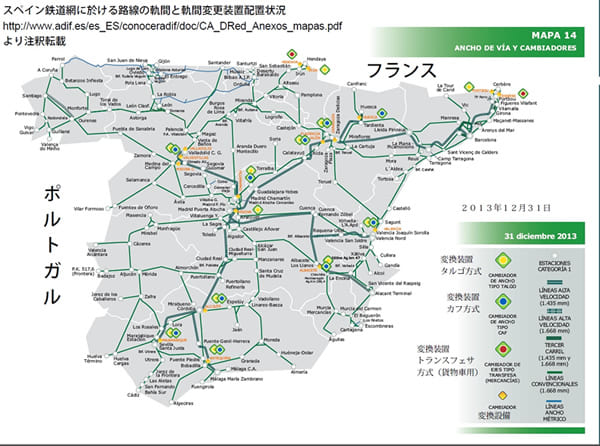

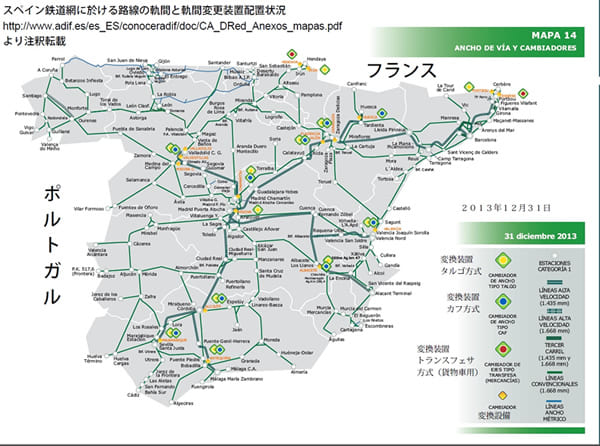

The Spanish high-speed rail network

The Spanish high-speed rail networkOriginally the Talgo company had developed a special type of train with wheels that rotated independently of each other, to allow them to travel quickly and safely along Spain’s curvy railways. This meant it was easier to change over to a system enabling the change in axle length compared to the standard carriages with the wheels fixed at either end of the axle. After the launch in 1992 in Spain of the AVE high-speed rail with its different rail gauge, the need arose to connect it to domestic conventional lines, not just international trains, so the railway carriage manufacturer CAF came onto the scene and enabled interoperable services between the different gauge lines using two systems. In 2013, 24 rail gauge changers were being operated at 17 changeover facilities across Spain. If you look at the network map, you will see there are none along the border with Portugal. Portugal uses the same gauge as Spain, so there is no problem with interoperability.

Location of automatic rail gauge changers (Source: Administrator of Railway Infrastructures (ADIF) website)

Location of automatic rail gauge changers (Source: Administrator of Railway Infrastructures (ADIF) website)While European countries use a standard gauge, Russia’s conventional rail gauge is wider (1,520 mm), which used to slow down services connecting with European countries. However, the Free Gauge Trains developed by Spanish company Talgo were brought in and services between Moscow and Berlin commenced on December 17, 2016. This new service has reduced travelling time from about 25 hours to 5.If this technology, which allows trains to run freely along railways of differing gauges, could connect the Trans-Siberian Railway, the longest in the world and the bridge between Russia and the far east now celebrating 100 years of operation, with the Hokkaido Shinkansen via Sakhalin, then you might get the departure board at Tokyo Station showing Europe Limited Express – Lisbon via Moscow & Berlin. Really?That was the wild idea I dreamt up one mid-summer night in the furnace of Madrid, my brain about to boil like a dotenabe hotpot.

The temperature gauge at my local hardware store showing a new record this year of 51 degrees (C) after last year’s 49 degrees.

The temperature gauge at my local hardware store showing a new record this year of 51 degrees (C) after last year’s 49 degrees.(※)AVE is the acronym for Alta Velocidad Española, which is pronounced “ave,” and means “Spanish high-speed (railway, train, line).” “Ave” also means “bird” in Spanish and the train logo is a bird with wings outspread. The AVE (pronounced “Abe” in Japanese) can travel along railways with a “mix” (“mikkusu” in Japanese) of different gauges, so it is also known (in Japanese) as “Abenomikkusu” (or “Abenomics” in English, from Japanese Prime Minister “Abe” and the Japanese words “no” [of] and “mikkusu” to render the double entendre “Abe’s mix”), but that has not been confirmed.

AVE reaches a maximum speed of 310 kmh. Occasionally, a bird (“ave”) clashes into the windshields of driver’s cabins. You can also see a railway worker cleaning the front of a train with a bucket of water after its arrival.

AVE reaches a maximum speed of 310 kmh. Occasionally, a bird (“ave”) clashes into the windshields of driver’s cabins. You can also see a railway worker cleaning the front of a train with a bucket of water after its arrival.

The taste of Japan I am looking forward to this summer: Edamame (green soybeans), the best snack to go with beer at the height of summer. “Edamame” 500 g, 1.6 euros (about ¥210)

The taste of Japan I am looking forward to this summer: Edamame (green soybeans), the best snack to go with beer at the height of summer. “Edamame” 500 g, 1.6 euros (about ¥210) The Spanish high-speed rail network

The Spanish high-speed rail network Location of automatic rail gauge changers (Source: Administrator of Railway Infrastructures (ADIF) website)

Location of automatic rail gauge changers (Source: Administrator of Railway Infrastructures (ADIF) website) The temperature gauge at my local hardware store showing a new record this year of 51 degrees (C) after last year’s 49 degrees.

The temperature gauge at my local hardware store showing a new record this year of 51 degrees (C) after last year’s 49 degrees. AVE reaches a maximum speed of 310 kmh. Occasionally, a bird (“ave”) clashes into the windshields of driver’s cabins. You can also see a railway worker cleaning the front of a train with a bucket of water after its arrival.

AVE reaches a maximum speed of 310 kmh. Occasionally, a bird (“ave”) clashes into the windshields of driver’s cabins. You can also see a railway worker cleaning the front of a train with a bucket of water after its arrival.