Fall in Japan comes with many events making it a busy season in one way or another. Just off the top of my head, it is, for example, a season of reading, appetite for food, art, harvests, and leisure trips. And of sport. I have always thought of fall as the best season. But it is actually summer that was determined to be the most suitable season for the major sport event whose success was to be underpinned by the spirit of “o-mo-te-na-shi” (“Japanese hospitality”) for athletes from all over the world to come together and compete under the best conditions.

Here in Madrid, summer was fiercely hot although shorter than usual and the signs are starting to emerge of fall, “when the horses fatten,” and I am closing the windows before going to bed. COVID-19 continues to spread, its end is nowhere in sight, we are still “living with COVID”—wearing masks, social distancing, working from home, and staying at home—the long vacation is over, and a new school term has started: it seems the cogwheels of daily life have started turning again.

But it isn’t as though we have changed clothes and suddenly plunged into fall mode. Even though people might think summer is over, every year around September 29, the feast day of San Miguel, there occurs a weather event in which it seems as though summer has returned, and the temperature suddenly rises. In Spanish, this is called “Veranillo de San Miguel,” or in English, “St. Michael's little summer.” Although the time of year differs slightly, Indian summers and Japanese “koharu biyori” (warm fall weather) are also unseasonal hot spells.

Another name for this Indian summer is “veranillo del membrillo,” after membrillo, a fruit that comes into season right around this time. The Japanese name for this fruit is "marumero" (quince) or “seiyo karin” (common medlar), which would make it a kind of “quince summer,” perhaps?

On the outside, quinces look like malformed apples or poorly formed nashi pears, and are actually hard and astringent on the inside, not good to eat raw. But if you stew them with sugar and process them into dulce de membrillo, a firm product like yokan (Japanese sweet bean jelly), you get an excellent dessert or snack. Eating it with cheese makes for a popular aperitivo (snack eaten with drinks) in Spain.

Photo 1

Photo 1: Photo of quinces grown in the orchards of a major quince processor, Membrillo Emilys (from the company’s website: https://emilyfoods.com/el-membrillo/)

Photo 2

Photo 2: Some dulce de membrillo, or “quince yokan” (as I call it), from the company I mentioned, which I bought at a supermarket, along with another Spanish specialty, Manchego cheese. This combination goes perfectly with red wine. In the same way that kaki yokan (persimmon jelly), which has a similar color and texture, goes with Japanese sake, it makes for a superb marriage of wine and sweetness.

In Japan, even the name "marumero" might not be widely known. But probably everyone has heard of marmalade. This type of jam is made by stewing citrus fruits and so on in sugar with their peels, and the name comes from the Portuguese word marmelada, which means “marmelo (quince) jelly.” In Spanish, the fruit is “membrillo” and the tree is “membrillero,” but the Portuguese word “marmelada” is also used in Spain for “marmalade.”

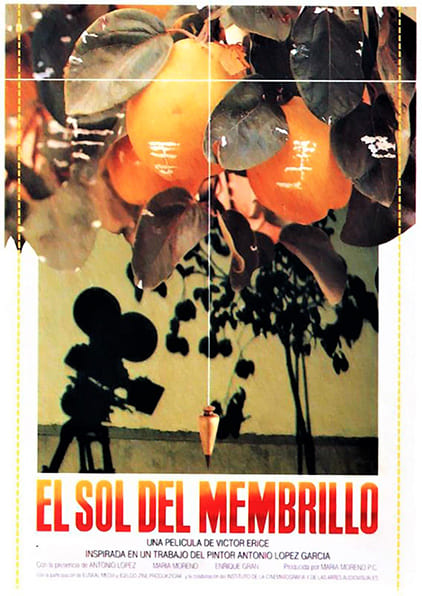

There is a film I always think of when I see or hear the word "membrillo:" El Sol Del Membrillo (Dream of Light), which was released in 1992, about 30 years ago. Its Japanese title is Marumero no Yoko (literally, “Quince Sunlight”). It is a gently moving film that simply records the emotional response of a painter to the sunlight and shadows cast by quinces growing on a tree he planted in the garden of his studio in Madrid, and follows the course of him creating a work of art around it.

It is the third feature film by director Victor Erice, who is otherwise known for creating only a few works. By the way, his first feature film was The Spirit of the Beehive in 1973, and his second was The South in 1983. That means he has made only three feature films in the 48 years since his feature debut.

Photo 3

Photo 4

Photo 5

Photo 3: This is the poster for his latest movie (1992!). The plumb bob, the carpenter's tool in the center, was used by the artist to accurately work out the perpendicularity, and to determine the center line, of the objects he painted. The fruit and leaves are also marked with white paint. The film opens with the main character arriving at his studio carrying some art supplies. The caption tells us "Madrid, Otoño 1990 Sábado 29 de Septiembre” (“Saturday September 29, 1990, Fall, Madrid”), which shows us that the painting and the filming started at the same time, on the feast day of San Miguel, when the summer sun returns.

The painter is Antonio López, dubbed a great painter of contemporary Spanish realism.

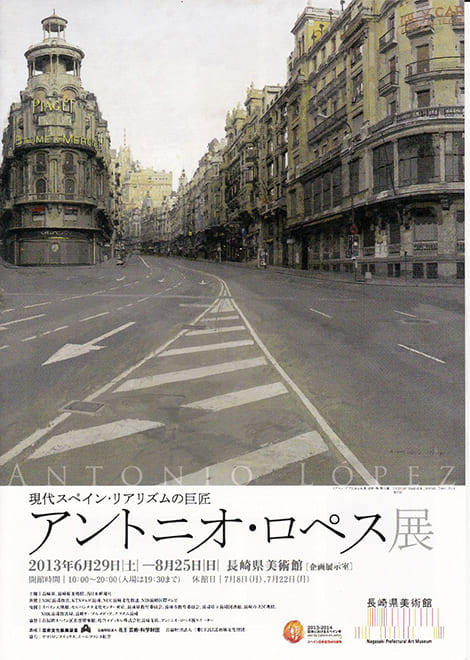

Photo 4 is a leaflet for his solo exhibition held at Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum, which has one of the best collections of Spanish art in the East. The work used here is one of his masterpieces: "La Gran Vía de Madrid” (“Madrid’s Gran Via”).

He was fascinated by the contrast between the top of the chalk-white Telefónica (telecommunications company) building visible in the background in the righthand part of the painting, which was beginning to sparkle in the light of the rising sun, and the street corner, which was still in shadow, with the silence of Madrid’s principal thoroughfare in the early morning. He completed the work over eight summers from 1974 to 1981 by repeatedly putting brush to canvas for only 20 to 30 minutes at a time, from around 6:30 in the morning (the time displayed on the electronic board on the building at left.) until the light penetration changed.

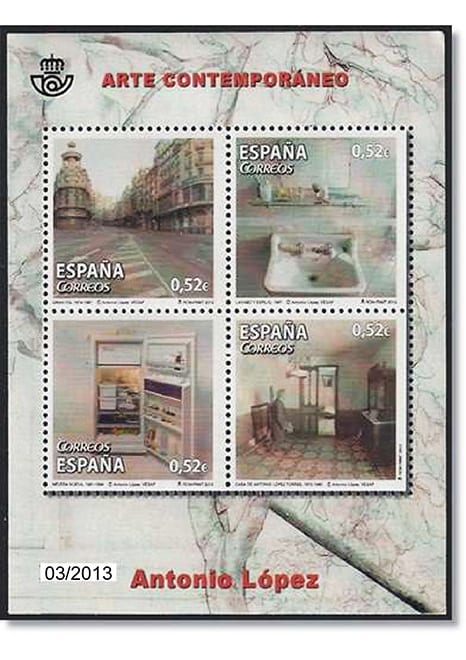

Photo 5: Four of his representative works, including this one, appear in the 2013 Spanish contemporary art stamp series.

Photo 6

Photo 6: "Membrillero” (“The Quince Tree”) is the work used for the banner hung in front of the Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum to publicize the venue at the time of his solo exhibition and El Sol Del Membrillo (Dream of Light) is the semidocumentary film I mentioned before that follows the course of him painting this work. Incidentally, in the last scene of the film the painter falls asleep. It ends inside his dream where we see rambling images, including his hometown village of Tomellosso, La Mancha, the square in front of the house where he was born, himself and his parents under a heavily laden quince tree, and the bustling of people.